Today’s birth story is one of my favorites because it was the very first time I had a student’s water break (release) in class, right in the middle of a meditation/relaxation exercise! It’s the story of a 5-hour, unmedicated vaginal birth, with some complications and a necessary surgical procedure after the birth due to how quickly the labor progressed. Listen as Brooke shares details about the overall compassionate care she received through the complications and how, when the staff clearly communicated with her what was going on, she felt taken care of and, overall, really positive about the way things went. After she shares her birth story, Brooke also discusses how her partner is enjoying being a stay-at-home for the first time after having 2 children in a previous relationship and not having the opportunity to stay home. She’ll also share insights about the surprising things you sometimes learn about yourself as you become a parent as well as tips for maintaining a healthy identity.

Read moreI've Given Birth to a Baby! (a baby PODCAST, that is)

Announcing the BIRTH MATTERS podcast! This show is here to lessen expectant parents’ overwhelm on the journey into parenthood by equipping and encouraging with current, evidence-based info & soulful interviews with parents & birth pros. It’s also here for birth professionals to continue growing their knowledge base, and even for anyone who is simply interested in birth.

Read more7 Great Reasons to Labor at Home

One of the smartest strategies for a healthy labor and birth for baby and mother is for a low-risk, healthy person to spend a lot of time laboring at home. How long, you ask? This will vary among individuals, as most things do, and will depend on whether or not the laborer is hoping to get the epidural or other pain meds. In general, I recommend laboring at home until the labor gains some good momentum. When this is done, we're strategically positioned for labor to progress in an optimal way because this momentum should help prevent labor from slowing down to an undesirable and unhelpful extent, which tends to happen as a simple result of leaving the safe space of our home and getting in that highly unpleasant car transfer. In general, this means staying at home until it's impossible to speak through contractions, contractions are lasting at least 1 minute and have been that way for over an hour. Let's go over the top reasons laboring at home is a wise idea.

1. First-time labors take plenty of time!

This 100% rocks the boat of everything we see in movies/tv, I know. So much of dramatized birth does, so let's get real here. Did you know that a first-time labor--from start to finish--usually takes an average of 18 hours? (You can read a more detailed breakdown of stage of labor with time estimates here, though it doesn't cover the pushing stage, which for first-time moms can take a while as well. You'll see there's a huge range of normal!)

Before you panic at this lengthy number and look for the quickest escape route, I want to point out that the vast majority of the time we spend in labor is the time spent in what we call "early" or 'latent" labor, which is the time when -- for the most part -- 1) the breaks in between contractions are much longer than the contractions (=the intense part), and 2) the contractions are quite manageable for most of early labor. It's also helpful to realize that, when you hear about the difference between, say, a 6-hour labor and a 26-hour labor, the difference can be attributed to the wide variability of time spent in early labor, when the sensations of labor are pretty manageable. Another factor is how early we notice: perhaps the 26-hour laborer just paid attention sooner than the 6-hour laborer. That 26-hour mama wanted the credit for all that hard work she and her baby did, and I don't blame her one bit! So, it's encouraging to point out that when we get into range of normal time ranges for active labor and beyond (read: when things get intense), the window of variable is much smaller.

Now that's we've established that there's no need to panic or rush when you think you're in labor, let's go over the good reasons to labor at home for a significant period of time:

2. Reduces chance of unnecessary intervention

The longer you can delay putting yourself on what tends to be a fairly arbitrary and impatient hospital "clock"--in which a cervix is expected to dilate at the rate of 1 cm an hour (unrealistic for organic and unique human beings)--the more wisely you position yourself strategically for avoiding unnecessary intervention. Unnecessary interventions are, logically, not healthy for anyone, tend to be unpleasant, and are more costly for you and/or our troubled U.S. healthcare system. There's something called the "Friedman's Curve" that propagates this trend. Read this article from Evidence Based Birth on how Friedman's Curve leads to unnecessary cesareans. Many hospitals -- particularly here in overpopulated NYC -- need to turn beds, too, which compounds the unfortunate sense of impatience.

3. Helps labor progress

In order for labor to progress in a healthy, unhindered fashion, we need to feel safe and have a sense of privacy. This is a physiological / hormonal fact that we go over in great detail in class. We tend to feel these things most readily in our home environment.

In Ina May's Guide to Childbirth, well-known midwife Ina May Gaskin details her hypothesis on the ways in which the cervix--while not technically a sphincter, as it would require having circular muscles to be defined as such--behaves similarly to our anal or vaginal sphincters, and how we need to be strategic toward helping the cervix to open effectively in labor. These points are:

- Sphincter muscles open more easily in a comfortable, intimate atmosphere where a woman feels safe.

- Sphincters do not respond to commands.

- The muscles are more likely to open if the woman feels positive about herself; where she feels inspired and enjoys the birth process.

- Sphincter muscles may suddenly close even if they have already dilated, if the woman feels threatened in any way.

So, because we do see these things occur in labor when a woman doesn't have a sense of privacy, this is another good argument for laboring at home.

4. No one telling you not to eat or drink

We know, we know, we know that it's an evidence-based course of action to eat and drink in labor. For heaven's sake, your body needs fuel for your indeterminate length! No marathon runner would ever not eat or drink for their whole marathon and be able to go the distance, and we know that labor is even harder work for the body. The main reason for restricting food and drink (known as "NPO" -- Latin "Nil per os" meaning "nothing by mouth") for so many years was mostly due to a very small risk of aspiration for anyone going under general anesthesia for a cesarean/surgical birth. This risk has gone down to almost nonexistent due to a) advances in anesthesia and b) the fact that it's rare for a pregnant parent to go under general for a cesarean. You can read the American Society of Anesthesiologists' November 2015 statement indicating laboring individuals should be allowed to have food in labor here. The other reason we commonly hear of withholding food and drink from the laboring woman is the risk that it will cause her to vomit. I believe a) most women will listen to their bodies and only eat when they don't think they'll be able to keep it down and b) if we miss that instinct and do eat and vomit, it actually can help labor progress and baby descend to a lower station, so we can cheer for progress if it happens a time or two! (I wouldn't recommend doing that in an exuberant way, though, partners, or you may get a swift kick to the groin.)

5. More flexibility for pain-coping techniques

You almost undoubtedly have more furniture, tools, food, and space to support you in comfort measures than you will at the hospital or birthing center. Immersion in a tub of water is called "nature's epidural" and can be powerfully effective for handling labor well before the water breaks; many hospitals don't have tubs available. The power and helpfulness of this and other tools you have more readily available at home cannot be underestimated, and can very often lead to reduced or eliminated need for pain medications.

6. “Safe” bacteria vs. “mean” bacteria

It's wise to minimize your exposure to the meaner bacteria that resides in the hospitals. Your body has built up antibodies against the meaner bacteria that exists in your home. Not so of the meaner bacteria in hospitals.

7. Save unnecessary trip(s) to hospital

The longer you labor at home, the less doubt there will be that you're in labor and the less likely it is you'll be sent home. You can skip the super un-fun experience of showing up a time or more and being sent right back home because you're not actually in labor or it's too early!

I repeat: First-time moms have plenty of time!

Just repeating that again for reinforcement...since the opposite (falsehood) is so ingrained in us through our westernized culture. Those stories you see in the news about people having babies in a cab/car, on a bridge, on the sidewalk are almost NEVER first-time moms! It drives me crazy that the news always omits this important detail.

Exceptions?

This won't be an exhaustive list, and you will want to check with your care provider for your specific case, but here are a few:

- If you get to a point in your labor when you feel that you won't relax into labor until you're at your birth place, maybe you should go. This will a safer bet if you're with both a patient care provider, and one you fully trust to not pressure unnecessary use of technology (monitoring and the like) or medications.

- If you have a deep gut instinct that something is wrong, definitely listen and heed this instinct. The trick here is that we first-time parents tend to not know the vast range of normal so that we tend to get that wise instinct mixed up with simple fear of the unknown (but most likely healthy). This is where professional labor support (aka doula) can really help to normalize the scary and identify if there really is some reason to call your care provider or go to the hospital/birthing center sooner.

- Along similar lines, the last thing we want to do is to make any decision (including laboring at home longer than is right for you) based in fear. We want to make decisions based out of a place of peace, trust and love, whatever that means for you. Aligning yourself with a care provider and birth place in which you have a high level of trust and sense of calm -- specifically, in terms of not pushing unnecessary interventions or being impatient. This is critical toward reducing fear about unnecessary interventions. Aligning yourself with a measured, calm provider who trusts birth as a healthy, normal process also could mean that the laborer doesn't necessarily need to labor at home quite as long.

- There will be other exceptions in which it's not advisable to labor at home for long. A few of the more common examples: if your water breaks and a) you are GBS+ (in the U.S. they'll want you to get 2 minimum rounds of IV antibiotics spaced 4 hrs apart to reduce the very small risk of harm to the baby), b) there are specks in the fluid, or c) if the fluid had a foul odor. Any of these would be indications to head to the hospital. Your care provider should give you a heads up in advance about anything that would be an indication to come to the hospital. You can always call your care provider to ask if you're unsure in the moment.

Okay, but HOW do I labor at home patiently?

"How in the world will I confidently labor at home as long as possible," you might ask, "when I've never done this before and every little thing seems scary?" I totally get it as I've been in your shoes! Let's talk specific strategies as we wrap things up.

- Ignore it (until you can't). Are you serious? Yes. Of course, ignoring labor is often easier said than done, but at first the contractions will be fairly mild (unless you ignored it and didn't realize it, which is pretty ideal!). You can plan ahead some "early labor activities" to have at the ready when the big day comes to help take your mind off labor. Make a list of half restful, half active things to do. Think along the lines of the more "normal" pastimes/hobbies -- i.e. things you like to do on the weekends or in your free time -- and prepare whatever items you'll need to have on hand for this. I will write a post on this in the near future, but here are just a few examples: taking a walk, walking the dog, some gentle yoga or exercise, making out or having sex if you're in the mood and waters haven't broken, cooking, baking (take treats for the nurses!), watching tv/movies (comedy would my top recommendation to promote oxytocin/endorphins, both of which help labor progress), etc. Oh, and if you wake in the middle of the night and think you're in labor, I highly recommend not waking your partner (if applicable). That's the quick route to not ignoring labor. Instead, do everything you can to go back to sleep--while you can!

- Build trust in and educate yourself on the process and the wide range of normal by taking birth classes (if you are in NYC, check out my birth classes!), reading or listening to positive birth stories (please note this podcast includes all kinds of birth stories, so judge for yourself based on the title whether or not it might build trust and calm for you). I also have several positive birth stories on my blog, so check those out (a couple of examples are here, here and here). Please note: "Dr. Google" is not your friend and will not build trust/calm for you! Find the trustworthy and evidence-based online resources and only refer to those.

- Consider hiring a doula, who can normalize the process, help you relax and boost the labor-promoting hormone, oxytocin, help you successfully surrender to the good work your body and your baby are doing toward birth, and ultimately labor at home much longer (read here to see the many more reasons this is a good idea!). A very smart investment toward a healthy birth.

Remember that you'll always be able to, if it helps you feel calmer laboring at home, interface with your care provider periodically. They'll probably appreciate having a heads up that you're in early labor. They will also appreciate that they don't need to come to the hospital or birthing center as early and should be happy to support you by phone to some extent. And, if they say to come to the hospital or birthing center before you feel ready--and in the absence of some legitimate medical reason to do so--you can simply say, "Thanks, but I think I'll stay home a bit longer." Your body, your baby, your call!

Patience, my friend. You can do this!

Cheers, ACOG: One childbirth educator's review of ACOG's new recommendations on reducing unnecessary interventions

Recently, American Congress of Obstetricians & Gynecologists issued a new list of recommendations on ways care providers and hospitals can reduce unnecessary interventions in labor/birth. Today I'll list select parts that reinforce and affirm things we childbirth educators have been teaching for a number of years...

Read more5 Benefits to Baby of Delayed Cord Clamping

Did you know that, for a few minutes after your baby is born, the placenta continues to serve as life support to the baby, with blood continuing to transfer from mom's body through the placenta and umbilical cord into baby? Did you know that allowing that blood to continue transferring to baby can increase blood volume by up to 1/3, thereby benefitting a newborn's lifelong health in significant ways? Yet in the U.S., the protocol in the vast majority of hospitals is to clamp the cord as soon as baby is born.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends delaying umbilical cord clamping for a minimum of one minute after a baby is born. Recently, the American Congress of Obstetricians & Gynecologists (ACOG) lengthened their recommendation, now saying to hold off clamping for at least 30-60 seconds post-birth. Many midwives and some OBs promote allowing the cord to stop pulsating before clamping it. You can also read a New York Times article commenting on this new recommendation here.

Why have hospitals historically clamped immediately?

Risk of maternal hemorrhage - Hospitals have routinely clamped immediately after birth with the intention of preventing maternal hemorrhage. However, a growing body of evidence in recent years indicates delaying the clamping some does not increase the risk of hemorrhage

Risk of neonatal jaundice - If baby gets extra blood, they'll get extra bilirubin, which could increase the risk of jaundice due to the fact that newborn livers have a low ability to process bilirubin out of the body efficiently due to an immature liver. However, treatment is readily available in most places (at least in the U.S.), and this is usually an easily treatable condition. For a mom who is breastfeeding, the more frequently she feeds baby, the quicker baby will poop out the bilirubin, thereby decreasing the risk of jaundice.

I want to point out here that the U.S. ranks terribly in maternal health (#61 in the world) and children's well-being (#42nd in the world), and the medical community is trying to find ways to rectify that. The change of recommendation with regard to delayed cord clamping is a small step away from active medical management (i.e., doing things actively to prevent a problem -- things that carry their own risk), toward expectant management (treating a problem only in the unlikely event that it arises).

Even so, research has revealed that hospitals take 15-17 years to change their protocols once evidence-based, revised recommendations are made. (Say whaaaa?! Yes, for real!) So, do not assume that your care provider will automatically default to delayed cord clamping. Always better to have a conversation with your care provider by around 36 weeks of pregnancy to make your request for delayed cord clamping--as well as any other birth preferences--known. I would recommend requesting your ideal, which could be to the longest end of the spectrum -- ie waiting until the blood has stopped flowing and the cord has stopped pulsating. Then you can negotiate down, if needed, based on the comfort level and rationale of your care provider.

Benefits to baby of delayed clamping

Extra blood to the lungs optimally supports baby's respiratory transition from womb to world

Around 3-6 months, many babies become a bit iron-deficient; iron is critical to brain development. Delaying the cord clamping can help prevent this by giving the baby extra iron stores. See this (aforementioned) study, which reports, "improvement in iron stores appeared to persist, with infants in the early cord clamping over twice as likely to be iron deficient at three to six months compared with infants whose cord clamping was delayed."

In this study, 4 year olds who had experience delayed cord clamping showed modestly higher scores in social skills and fine motor skills (though only for boys)

Increases early hemoglobin concentrations (hemoglobin is necessary for carrying oxygen from the lungs to the body's tissues and returning carbon dioxide from the tissues back to the lungs)

Many more benefits have been proven in preemies (also here and here)

Source: nurturingheartsbirthservices.com -- showing time lapse from birth to 15 minutes later.

Common Questions

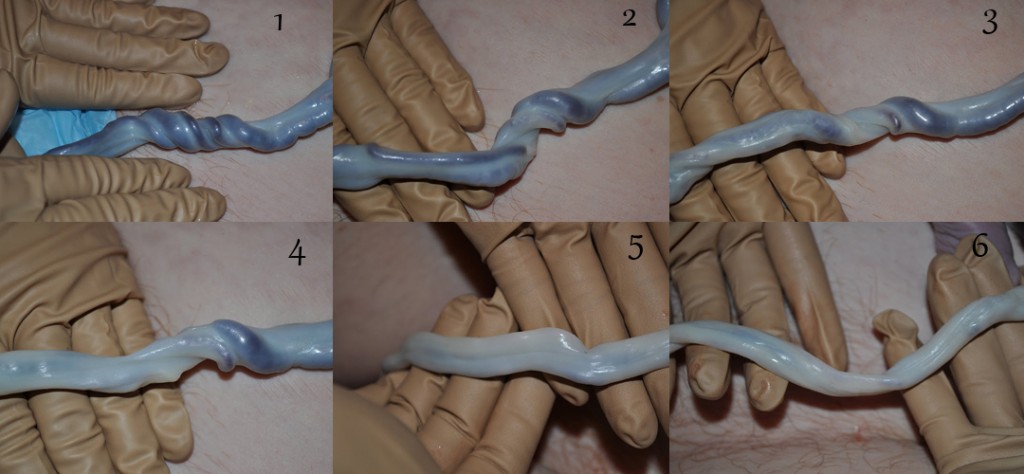

Is it helpful to milk the cord?

You may have heard of "milking" the cord, a way that some care providers try to "expedite" the transferral of blood to baby, there is no evidence this is a recommended alternative. What we are talking about here is leaving nature alone and letting the body, the placenta and the baby do the business of healthy blood transfusion for a few minutes uninterrupted.

If I'm given the scissors to cut my baby's cord, can't I just hold onto them to delay clamping?

No. Since your care provider will first clamp the cord an inch or so out from the belly button and then another inch or two out to stop the flow of blood before the scissors cut the cord.

Is it possible to do both delayed cord clamping and collect for cord blood banking?

The vast majority of care providers will indicate this is not possible, and they are perhaps right, but not necessarily. That is, we have no way of knowing how long the cord will pulsate or how much blood will pump through the cord before the placenta detaches from the uterus and be birthed. Therefore, it would be a gamble to try to delay the clamping and then also try to collect enough blood for cord blood banking. At this point in time, I am of the opinion that--if your care provider can't do both and you have to choose--it's better for babies to receive the blood that belongs to them right at birth (plus, it's free!). That is, unless any of the few known treatable illnesses with cord blood banking run in your family; this could be the exception to the rule.

Conclusion

Delayed cord clamping (waiting at least 1 minute and ideally until the cord has stopped pulsating) is evidence-based and best for your newborn's health. As with most things in birth, we need to do a risk/benefit analysis when deciding which parts of birth need to be medically managed, if any. This is one of many examples that the pendulum historically swung too far in the active/medical management direction and is starting to swing back toward the other--in this case, toward improved global children's health.

Resources

American Congress of Obstetricians & Gynecologists (ACOG) Jan 2017 revised recommendation

"Delayed Umbilical Cord Clamping May Benefit Children Years Later" (NPR)

"Delayed Cord Clamping Should Be Standard Practice in Obstetrics" - Academic OBGYN

"Doctors No Longer Rush to Cut the Umbilical Cord" (New York Times)